There has been a lot of talk about Christian “deconstruction” in the last several years. That is the current term being used to describe one’s move from faith to unbelief. Trends in the United States have shown a marked decline in religious affiliation.[1] In 2019, Lifeway Research found that more Protestant churches closed their doors than were planted that year.[2] Since COVID, the shift is no doubt more severe and for many Christian leaders, quite concerning. In this climate, it is not uncommon for pastors to have conversations with current or former churchgoers—especially within the younger demographic—who are at some stage of the process of losing their faith. The conversations typically involve questions about the Bible. Questions about errors or the accuracy of the text and whether we can trust the reliability of the accounts we find in the Gospels. I have had more than a few of these conversations. When I do, it is not infrequent that I hear the name Bart Ehrman.

Bart Ehrman is a New Testament scholar and textual critic. His books and debates are well-known in apologetic circles. They are also the regular fare of those on the path to unbelief. Before his own deconversion, Ehrman was an evangelical Christian. He had a “Born Again” experience in high school. Afterward, he attended Moody Bible Institute and Wheaton College and received a Ph.D. at Princeton Theological Seminary under the famed biblical scholar and Bible translator Bruce Metzger. Though Ehrman is an academic—serving as the James A. Gray Distinguished Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill since 1988—he writes for a popular audience. Bart’s books are required or recommended in many college classes on religion and Christianity.

Bart’s books are also filled with bold declarations about the inaccuracy and untrustworthiness of the Bible. This is why they so frequently surface in conversations with those questioning their faith. But along with his bold claims, Ehrman rarely presents the whole picture. For example, in his book Jesus Before the Gospels, Ehrman writes,

The first thing to emphasize about Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John is that all four are completely anonymous. The authors never indicate who they are. They never name themselves. They never give any direct, personal identification of any kind whatsoever.[3]

A few pages later, Ehrman goes on, “In short, the Gospel writers are all anonymous. None of them gives us any concrete information about their identity.”[4] Bart loves to point out that none of the earliest Gospel manuscripts contain the names Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John. That is somewhat accurate. But that isn’t the whole story. What is?

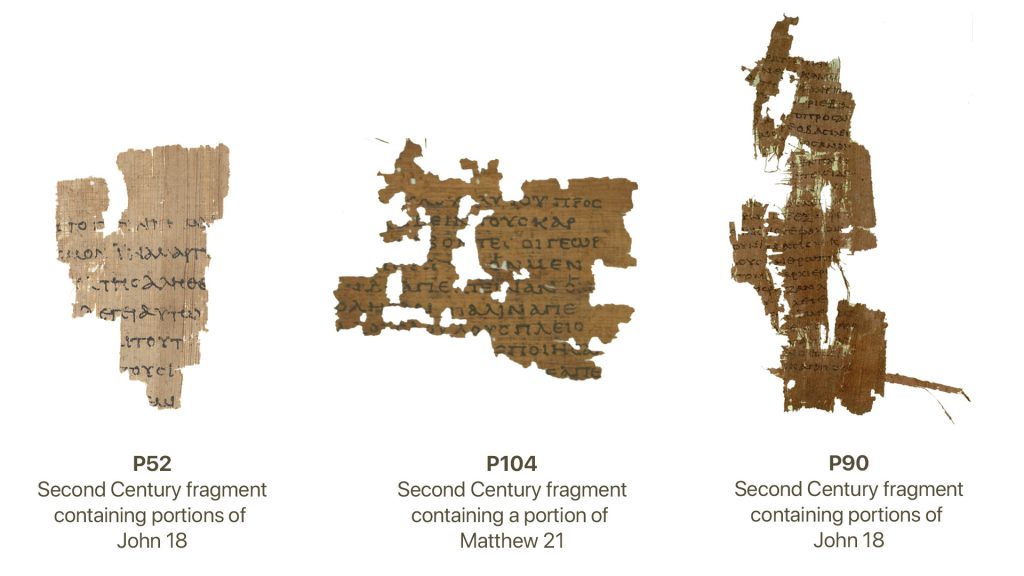

The more detailed picture is that while it is true the earliest surviving Gospel manuscript fragments do not contain the names Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John, these fragments are so small that they provide no evidence one way or the other about what names may have been present in the original documents.

Additionally, the earliest, more complete Gospel manuscripts we possess do in fact bear the titles “According to Matthew,” “According to Mark,” and so on. Moreover, Bart fails to account for the strong and early historical attestation from early church writings about the Gospels’ authorship. Some of the early church fathers in the second century attribute the Gospels to their traditionally ascribed authors. For example, Irenaeus of Lyon (c. 130–202 AD) was an early Christian theologian. Though he served in Gaul, he was originally from Smyrna, in Asia Minor. He played a role in establishing (or validating) the canon of the New Testament and also identified the authors of the Canonical Gospels. Eusebius of Caesarea recorded Irenaeus’ words:

Matthew published his Gospel among the Hebrews in their own language, while Peter and Paul were preaching and founding the church in Rome. After their departure Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, also transmitted to us in writing those things which Peter had preached; and Luke, the attendant of Paul, recorded in a book the Gospel which Paul had declared. Afterwards John, the disciple of the Lord, who also reclined on his bosom, published his Gospel, while staying at Ephesus in Asia.[5]

In addition to Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria (c. 198 AD) expressly affirmed that “there are four, and only four ‘traditional’ Gospels that the church receives: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.” [6] Justin Martyr (writing ca. 150–160) wrote of plural “gospels,” and his student Tatian recognized four canonical Gospels. We could also turn to the writings of Papias and the evidence of the Muratorian Canon, but suffice it to say that manuscript evidence throughout the early Christian world shows a consistent attestation to four Gospels. Each time they bear the names Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. The consistent attribution suggests that the names of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were firmly attached to these texts very early in Church history.

When one considers the full range of evidence, it seems that Ehrman presents an incomplete picture by claiming that the Gospels are wholly anonymous without qualification. The weight of the historical evidence suggests that the traditional Gospel authorship attributions were established very early in the transmission process, likely as soon as the texts began to be circulated. While the titles may not have been affixed to the original autographs, the agreement of authorship ascription in the early church suggests that the traditional authors were associated with the Gospels at a very early stage, contrary to Ehrman’s unqualified claims of anonymity. Though struggling believers may wrestle with fair critiques from Ehrman, the issue of Gospel authorship has reasonable answers when one examines the scholarship and historical evidence.

Photo by Max Tcvetkov on Unsplash

[1] https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/12/14/about-three-in-ten-u-s-adults-are-now-religiously-unaffiliated/

[2] https://www.npr.org/2023/05/17/1175452002/church-closings-religious-affiliation#:~:text=Estimate%3A%20In%202019%2C%20the%20year,opened%20and%204%2C500%20churches%20closed.

[3] Ehrman, 105

[4] Ehrman, 108

[5] Eusebius of Caesaria, “The Church History of Eusebius,” in Eusebius: Church History, Life of Constantine the Great, and Oration in Praise of Constantine, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, trans. Arthur Cushman McGiffert, vol. 1, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1890), 222.

Miles is the senior pastor of Cross Connection Church in North San Diego County, California. He serves as a board member at Enduring Word and Blue Letter Bible.

Miles has a master of divinity degree from Gateway Seminary in California, and is finishing a doctor of educational ministry at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kentucky.

Miles and his wife Andrea have four children, two dogs, three rabbits, a tortoise, a chinchilla, a hamster, a cat, and a crested gecko.